Difference between revisions of "Mechanism of Mosaic Split"

Paul Patton (talk | contribs) |

m |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

|Question=What happens to a mosaic when two or more similar theories are considered equally acceptable by a '''scientific community'''? Under what conditions does a '''mosaic split''' occur? What happens to a ''mosaic'' when it is transformed into two or more ''mosaics''? | |Question=What happens to a mosaic when two or more similar theories are considered equally acceptable by a '''scientific community'''? Under what conditions does a '''mosaic split''' occur? What happens to a ''mosaic'' when it is transformed into two or more ''mosaics''? | ||

|Topic Type=Descriptive | |Topic Type=Descriptive | ||

| − | |Description=There have been many cases in the history of science when one community divided into two or more communities. These distinct communities would then have their own distinct theories and methods. For example, consider the case outlined by [[Hakob Barseghyan|Barseghyan]] of the | + | |Description=There have been many cases in the history of science when one community divided into two or more communities. These distinct communities would then have their own distinct theories and methods. For example, consider the case outlined by [[Hakob Barseghyan|Barseghyan]] of the distinct mosaics of French and English natural philosophers in the early part of the 18th century, wherein the former accepted a version of Cartesian theory while the latter accepted a version of Newtonian theory.[[CiteRef::Barseghyan (2015)|p. 203]] We can see by various indicators[[CiteRef::Barseghyan (2015)|pp. 113-120]] that the dispute between these two communities was not a simple matter of scientific disagreement within a community such as we might observe in the contemporary dispute between various interpretations of quantum mechanics. The Copenhagen Interpretation is generally regarded as the accepted view [[CiteRef::Faye (2014)]] but a number of other alternatives are advocated by various individuals within the field. As note by Barseghyan, it this is a perfectly acceptable situation so long as the individuals acknowledge that the ''accepted'' theory is that the Copenhagen Interpretation is accepted as the best description of its object.[[CiteRef::Barseghyan (2015)|p. 202]] A contender theory might be said to be [[Theory Pursuit|pursued]] but this is perfectly consistent with our present understanding of scientific change. |

What makes the situation in the case of the 18th century French and English mosaics distinct is that the communities [[Theory Acceptance|accepted]] the Cartesian and Newtonian physics as the best description of the physical reality. In this case we justified as regarded these as distinct epistemic communities which each bears its own mosaic. Understanding the mechanism by which this sort of situation occurs is among the goals of a general descriptive theory of scientific change. | What makes the situation in the case of the 18th century French and English mosaics distinct is that the communities [[Theory Acceptance|accepted]] the Cartesian and Newtonian physics as the best description of the physical reality. In this case we justified as regarded these as distinct epistemic communities which each bears its own mosaic. Understanding the mechanism by which this sort of situation occurs is among the goals of a general descriptive theory of scientific change. | ||

Revision as of 14:02, 15 January 2018

What happens to a mosaic when two or more similar theories are considered equally acceptable by a scientific community? Under what conditions does a mosaic split occur? What happens to a mosaic when it is transformed into two or more mosaics?

There have been many cases in the history of science when one community divided into two or more communities. These distinct communities would then have their own distinct theories and methods. For example, consider the case outlined by Barseghyan of the distinct mosaics of French and English natural philosophers in the early part of the 18th century, wherein the former accepted a version of Cartesian theory while the latter accepted a version of Newtonian theory.1p. 203 We can see by various indicators1pp. 113-120 that the dispute between these two communities was not a simple matter of scientific disagreement within a community such as we might observe in the contemporary dispute between various interpretations of quantum mechanics. The Copenhagen Interpretation is generally regarded as the accepted view 2 but a number of other alternatives are advocated by various individuals within the field. As note by Barseghyan, it this is a perfectly acceptable situation so long as the individuals acknowledge that the accepted theory is that the Copenhagen Interpretation is accepted as the best description of its object.1p. 202 A contender theory might be said to be pursued but this is perfectly consistent with our present understanding of scientific change. What makes the situation in the case of the 18th century French and English mosaics distinct is that the communities accepted the Cartesian and Newtonian physics as the best description of the physical reality. In this case we justified as regarded these as distinct epistemic communities which each bears its own mosaic. Understanding the mechanism by which this sort of situation occurs is among the goals of a general descriptive theory of scientific change.

In the scientonomic context, this question was first formulated by Hakob Barseghyan in 2015. The question is currently accepted as a legitimate topic for discussion by Scientonomy community.

In Scientonomy, the accepted answers to the question can be summarized as follows:

- When two mutually incompatible theories satisfy the requirements of the current method, the mosaic necessarily splits in two. When a theory assessment outcome is inconclusive, a mosaic split is possible. When a mosaic split is a result of the acceptance of only one theory, it can only be a result of inconclusive theory assessment.

Contents

Broader History

Traditionally the topic of why communities of scientists accept different theories has been an enigma for historians and philosophers of science, although the problem has been known about for some time. In the Categories for example, Aristotle grappled with the question of false belief and how false beliefs came to be acquired, and the significance of the question for science and epistemology.3pp. 289-290 While it is true that we are no longer so interested in the question of false beliefs but are instead interested in the question of divergent beliefs the central question of how different beliefs arise in epistemic communities remains the same.

Pre-Kuhnian philosophers' typical response to divergent community beliefs has largely depended on their views of scientific change more generally. An example of this is the work of Karl Popper. Popper regarded scientific change as being a process of conjectures and refutations, "of boldly proposing theories; of trying our best to show that these are erroneous; and of accepting them tentatively if our critical efforts are unsuccessful".4p. 68 Thus, Popper's approach suggested that any difference in the beliefs of certain communities could be chalked up to differences either in available knowledge (whether a conjecture had been refuted) or a difference in experimental methods (whether the same criteria were being applied in refutations). The difference between philosophers of science in this period more generally was their views on how science changes; this in turn coloured what factors (or mistakes) present in difference communities were relevant to divergent scientific beliefs. This form of thinking with regards to differences of thought on scientific theories - if not the exact formulation it takes - was generally held by "positivists" or "logical empiricists" and accepted until the historical turn in the 1960s.5p. 4

It was with the emergence of Thomas Kuhn's Structures of Scientific Revolutions in the 1960s that the consensus about divergent beliefs was challenged.6 Kuhn's "revolutionary" approach to scientific change radically diverged from his predecessors. On this view science has periods of normal science wherein the prevailing dogmas and core theories (the paradigm) are unquestioned and science proceeds as a process of puzzle solving; this is followed by a crisis in which mounting anomalies cause scientists to question the theoretical foundations of the paradigm.7 Crises may have no impact on normal science or they may result in a revolution, what Kuhn calls "the emergence of a new candidate for paradigm and with the ensuing battle over its acceptance".7p. 84 The present question of how divergent beliefs arise within communities fits nicely into this framework - a unified community starts by doing normal science, anomalies emerge within the paradigm, and a revolution occurs which splits the community. Subsequent work by philosophers in the field of scientific change would be coloured by the same kind of analysis of the historical record that shaped Kuhn's view of the subject, including the work done by Imre Lakatos, Paul Feyerabend, and Larry Laudan.5p. 5

One other approach to divergent community beliefs that deserves mention is the approach taken by the social sciences, namely the sociology of scientific knowledge (SSK) advanced principally by David Bloor.8 SSK regards scientific activity to be indistinct from other kinds of human social activity and as such and area that falls under the purview of the social sciences.9 As such, any divergence in community beliefs is the result of and explainable by sociological factors that contribute to belief formation.

Scientonomic History

This question was proposed by Hakob Barseghyan in 2015 with the publishing of the Laws of Scientific Change.1

Acceptance Record

| Community | Accepted From | Acceptance Indicators | Still Accepted | Accepted Until | Rejection Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scientonomy | 1 January 2016 | This is when the community accepted its first answers to this question, the Necessary Mosaic Split theorem (Barseghyan-2015) and the Possible Mosaic Split theorem (Barseghyan-2015), which indicates that the question is itself considered legitimate. | Yes |

All Theories

| Theory | Formulation | Formulated In |

|---|---|---|

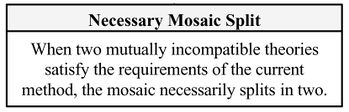

| Necessary Mosaic Split theorem (Barseghyan-2015) | When two mutually incompatible theories satisfy the requirements of the current method, the mosaic necessarily splits in two. | 2015 |

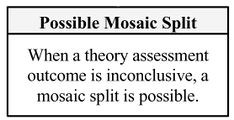

| Possible Mosaic Split theorem (Barseghyan-2015) | When a theory assessment outcome is inconclusive, a mosaic split is possible. | 2015 |

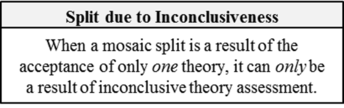

| Split Due to Inconclusiveness theorem (Barseghyan-2015) | When a mosaic split is a result of the acceptance of only one theory, it can only be a result of inconclusive theory assessment. | 2015 |

If an answer to this question is missing, please click here to add it.

Accepted Theories

| Community | Theory | Accepted From | Accepted Until |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scientonomy | Necessary Mosaic Split theorem (Barseghyan-2015) | 1 January 2016 | |

| Scientonomy | Possible Mosaic Split theorem (Barseghyan-2015) | 1 January 2016 | |

| Scientonomy | Split Due to Inconclusiveness theorem (Barseghyan-2015) | 1 January 2016 |

Suggested Modifications

Current View

In Scientonomy, the accepted answers to the question are Necessary Mosaic Split theorem (Barseghyan-2015), Possible Mosaic Split theorem (Barseghyan-2015) and Split Due to Inconclusiveness theorem (Barseghyan-2015).

Necessary Mosaic Split theorem (Barseghyan-2015) states: "When two mutually incompatible theories satisfy the requirements of the current method, the mosaic necessarily splits in two."

Necessary mosaic split is a form of mosaic split that must happen if it is ever the case that two incompatible theories both become accepted under the employed method of the time. Since the theories are incompatible, under the zeroth law, they cannot be accepted into the same mosaic, and a mosaic split must then occur, as a matter of logical necessity.1pp. 204-207 The necessary mosaic split theorem is thus required to escape the contradiction entailed by the acceptance of two or more incompatible theories. In a situation where this sort of contradiction obtains the mosaic is split and distinct communities are formed each of which bears its own mosaic, and each mosaic will include exactly one of the theories being assessed. By the third law, each mosaic will also have a distinct method that precludes the acceptance of the other contender theory.

Possible Mosaic Split theorem (Barseghyan-2015) states: "When a theory assessment outcome is inconclusive, a mosaic split is possible."

Possible mosaic split is a form of mosaic split that can happen if it is ever the case that theory assessment reaches an inconclusive result. In this case, a mosaic split can, but need not necessarily, result.1pp. 208-213 That is, "the sufficient condition for this second variety of mosaic split is an element of inconclusiveness in the assessment outcome of at least one of the contender theories".1p. 208

Barseghyan notes that, "if there have been any actual cases of inconclusive theory assessment, they can be detected only indirectly".1p. 208 Therefore:

One way of detecting an inconclusive theory assessment is through studying a particular instance of mosaic split. Unlike inconclusiveness, mosaic split is something that is readily detectable. As long as the historical record of a time period is available, it is normally possible to tell whether there was one united mosaic or whether there were several different mosaics. For instance, we are quite confident that in the 17th and 18th centuries there were many differences between the British and French mosaics.1p. 208

Thus, the historical examples of mosaic split below also serve as points of detection for historical instances of inconclusive theory assessment.

Split Due to Inconclusiveness theorem (Barseghyan-2015) states: "When a mosaic split is a result of the acceptance of only one theory, it can only be a result of inconclusive theory assessment."

Split due to inconclusiveness can occur when two mutually incompatible theories are accepted simultaneously by the same community.

Related Topics

This question is a subquestion of Mechanism of Scientific Change.

It has the following sub-topic(s):

This topic is also related to the following topic(s):

References

- a b c d e f g h i Barseghyan, Hakob. (2015) The Laws of Scientific Change. Springer.

- ^ Faye, Jan. (2014) Copenhagen Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics. In Zalta (Ed.) (2016). Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/qm-copenhagen/.

- ^ Miller, Fred D. (2013) Aristotle on Belief and Knowledge. In Anagnostopoulos and Miller (Eds.) (2013), 285-307.

- ^ Popper, Karl. (1963) Conjectures and Refutations. Routledge.

- a b Laudan, Rachel; Laudan, Larry and Donovan, Arthur. (1988) Testing Theories of Scientific Change. In Donovan, Laudan, and Laudan (Eds.) (1988), 3-44.

- ^ Bird, Alexander. (2008) The Historical Turn in the Philosophy of Science. In Psillos and Curd (Eds.) (2008), 67-77.

- a b Kuhn, Thomas. (1962) The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Bloor, David. (1976) Knowledge and Social Imagery. Routledge and K. Paul.

- ^ Longino, Helen. (2015) The Social Dimensions of Scientific Knowledge. In Zalta (Ed.) (2016). Retrieved from http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2016/entries/scientific-knowledge-social/.