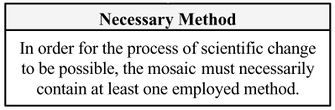

Necessary Method theorem (Barseghyan-2015)

This is an answer to the question Necessary Methods that states "In order for the process of scientific change to be possible, the mosaic must necessarily contain at least one employed method."

Necessary Method theorem was formulated by Hakob Barseghyan in 2015.1 It is currently accepted by Scientonomy community as the best available answer to the question.

Contents

Broader History

Insofar as necessary methods go, the philosophy of science was initially not very concerned with this subject. Philosophers like the logical positivists, Karl Popper, and all those up until Thomas Kuhn held the general tacit belief that there was a singular method of science and that all scientific communities would abide by it. This method was inherently necessary because science was exclusively a function of it; to believe otherwise would imply irrationality in science. For example, with Popper, theories were accepted on a basis of falsification and corroborated content.2 During this time, anything accepted without a method of acceptance was simply unscientific.

However, with the arrival of Kuhn and the fluidity of methods, the necessity of methods could finally come into question – though not specifically by him. Kuhn posited periods of normal science, which followed a certain method, but were eventually overtaken by anomalies and faced scientific revolutions. After a scientific revolution everything would be overturned and a new method would be taken on within the period of normal science. 3pp. 62-76Albeit Kuhn did not consider the necessity of methods discretely, it would seem in his formulations he determined a strict structure including methods. Therein, it would be fair to conclude he would have believed methods to be necessary. Additionally, Kuhn’s ideas gave rise to similar formulations by authors such as Imre Lakatos.

Like Kuhn, Lakatos believed there were several paradigms in scientific communities throughout history. Unlike Kuhn, Lakatos stipulated theories must be assessed holistically and with a singular method. Additionally, he posited there were many research programmes which were at war with each other instead of just a single paradigm. Theories were judged to be regressive or progressive via a fitting criterion which we can interpret as Lakatos’ method.4pp. 31-34 Once again, we see the acceptance of the necessity of methods within the community of the philosophy of science. Generally, it is not until the likes of Paul Feyerabend at which point the necessity of methods is rejected. However, very few philosophers of science to this day hold this view.

Scientonomic History

Acceptance Record

| Community | Accepted From | Acceptance Indicators | Still Accepted | Accepted Until | Rejection Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scientonomy | 1 January 2016 | The theorem became de facto accepted by the community at that time together with the whole theory of scientific change. | Yes |

Question Answered

Necessary Method theorem (Barseghyan-2015) is an attempt to answer the following question: Are there methods that are necessarily part of any mosaic? What methods, if any, are necessary for the process of scientific change to occur?

See Necessary Methods for more details.

Description

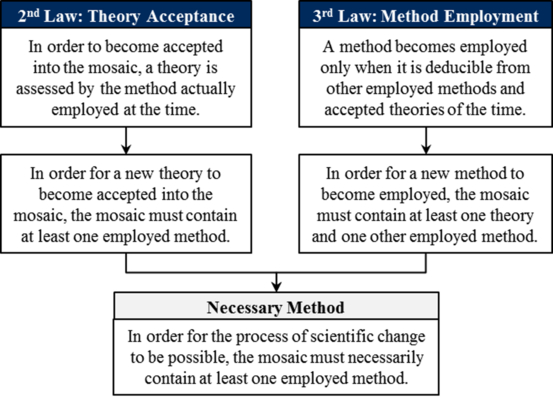

According to the non-empty mosaic theorem, there must be at least one element present in a mosaic. The Necessary Method theorem specifies that this element must be a method. That is, "one method is a must for the whole enterprise of scientific change to take off the ground".1p. 228

What would this method be? As per Barseghyan (2015):

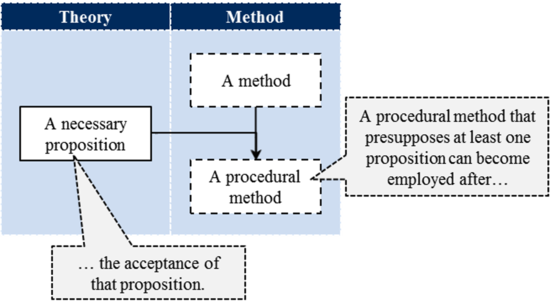

This necessary method cannot be substantive. Since a substantive method is necessarily based on at least one contingent proposition, it is not a necessary element of any mosaic. Indeed, any substantive method can become employed after the acceptance of those contingent propositions on which it is based. Of course, in some mosaics, substantive methods can also be present from the outset. Moreover, it is quite likely that even the earliest of mosaics tacitly contained some primitive substantive methods (e.g. “trust your senses”, or “trust the chieftain”). Yet, the key theoretical point is that no substantive method is necessarily part of any mosaic, for a substantive method can become employed after the acceptance of the theories on which it is based.

Therefore, the necessary method is not substantive, but procedural, i.e. it doesn’t presuppose any contingent propositions. But it is a procedural method of a very special kind in that it cannot presuppose any propositions whatsoever: "the method that is necessarily present in any mosaic is not based on any propositions".1p. 230

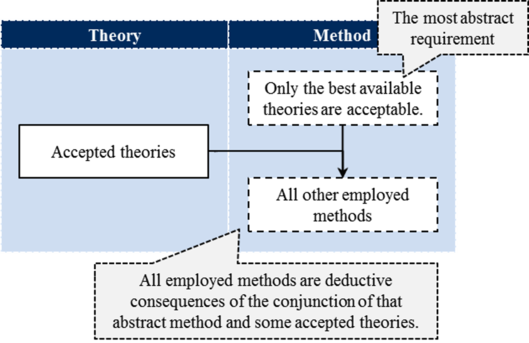

In other words, it must be the most abstract of all methods. Any concrete method is an implementation of a more abstract method. Any concrete method is a logical consequence of the conjunction of some accepted theories and that abstract method (by the third law). Thus, a concrete method can become employed after the acceptance of the propositions on which it is based. Therefore, what we are looking for is the most abstract of all possible requirements.

We have come across that requirement on many occasions: the most abstract requirement to accept only the best available theories. This basic requirement is the most abstract of all, for it does not presuppose any other methods or theories. It is not surprising given that this abstract method is only a restatement of the definition of acceptance: this abstract method basically says that a theory is acceptable when it is the best available description of its object. But since this abstract requirement isn’t based on any theories, it cannot become accepted; it must be built into any mosaic from the outset.

As vague and unrestricting as this method is, it nevertheless performs two very important functions. First, it indicates the main goal of the whole scientific enterprise – the acquisition of best available descriptions. Second, being a link between accepted theories and more concrete methods, it allows us to modify our methods as we learn new things about the world, i.e. it allows for concrete methods to become employed as we accept new theories. In short, it is this abstract requirement that makes the process of scientific change possible.1pp. 230-231

That is, any other method can be conceived as a deductive consequence of the conjunction of this abstract method and some accepted theories:

The gist of this theory can be illustrated by the following examples.

A necessary method cannot be substantive: Testability

The requirement of 'testability', according to which a scientific theory must be empirically testable, is often portrayed as "one of the prerequisites of science" though it is by no means a necessary element in any mosaic. Barseghyan (2015) develops the case study as follows:

The explanation is simple: the requirement of testability is substantive and, therefore, we can easily conceive of a mosaic where it is not present. It is substantive for it is based, among other things, on such a non-trivial assumption as “observations and experiments are a trustworthy source of knowledge about the world”. Thus, the requirement is not a necessarily a part of any mosaic; it can become employed after the acceptance of the assumptions on which it is based. The historical record confirms this conclusion. It is well known that testability hasn’t always been among the implicit requirements of the scientific community. For example, it played virtually no role in the Aristotelian-medieval mosaic.5p. 139 The same holds for any substantive method. For instance, the oft-cited requirement of repeatability of experiments is evidently part of our current mosaic, but not of every possible mosaic. Similarly, the requirement to avoid supernatural explanations is implicit in our contemporary mosaic, but it is not a necessary part of any mosaic.5p. 229

Hypothetical Community

To better illustrate this theorem, we can imagine a community with a set of accepted propositions.

Community φ accepts proposition α. For α to have become accepted, through the second law, we know that φ must have had implicit expectations which α satisfied. No matter what those expectations are, if the community had not harbored those expectations there could be no acceptance.

Similarly, if we have a community φ which experiences a change of expectations (i.e. a change of method), it is deductively true that φ already had a set of expectations which could be referred to as a method.Procedural methods that presuppose propositions are not necessary methods

To show why a necessary method must not presuppose any necessary propositions, we will consider a procedural method that does presuppose some necessary propositions:

Let it be the prescription that “if a proposition is deductively inferred from other accepted propositions, it must also be accepted”. As we know, this abstract method of deductive acceptance is procedural, as it is based on the definition of deductive logical inference.420 Now, it is obvious that this procedural method can become employed after the acceptance of the proposition on which it is based. Therefore, this procedural method is not necessarily part of any possible mosaic. The same applies to any procedural method that presupposes at least one necessary proposition. Such methods aren’t necessarily present in any mosaic, for they can be employed after the acceptance of the necessary propositions on which they are based.1pp. 229-230

Many different theories satisfy the abstract requirement

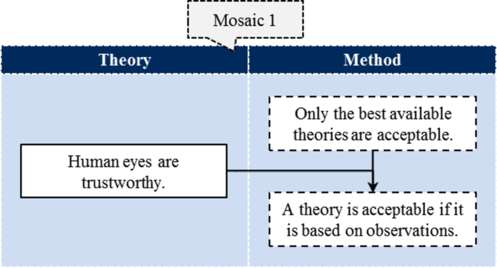

Most theories can satisfy the abstract requirement of the necessary method. Barseghyan (2015) outlines the following example:

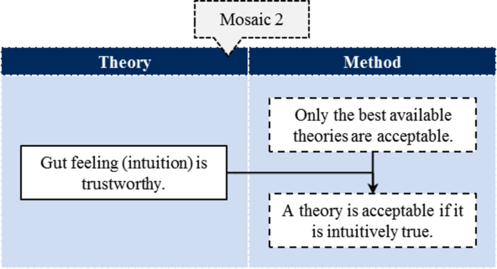

Imagine a community with no initial beliefs whatsoever trying to learn something about the world. In other words, the only initial element of their mosaic is the abstract requirement to accept only the best available theories. Now, suppose they come up with all sorts of hypotheses about the world. Since their method is as inconclusive as it gets, chances are many of the hypotheses will simultaneously “meet their expectations”. In such circumstances, different parties will most likely end up accepting different theories, i.e. multiple mosaic splits are virtually inevitable. For example, while some may come to believe that our eyes are trustworthy, others may accept that intuitions (or gut feelings) are the only trustworthy source of knowledge. As a result, the two parties will employ different concrete methods (by the third law) and will end up with essentially different mosaics.1pp. 231-232

These examples are not altogether fictitious. It is possible that something along these lines happened in ancient Greece, where some schools of philosophy accepted that the senses are, by and large, trustworthy, while other schools held that the senses are unreliable and that the only source of certain knowledge is divine insight (intuition). Thus, the historical fact of the existence of diverse mosaics in the times of Plato and Aristotle shouldn’t come as a surprise. As a result, at early stages, multiple mosaic splits are quite likely.1pp. 233

Reasons

Reason: Deduction of the Necessary Method Theorem

Barseghyan's explanation of the deduction is as follows:1pp. 227-228

By the Non-Empty Mosaic theorem, any mosaic contains at least one element, which is either a theory or a method. But which one is it: is it a theory or is it a method? It is easy to see that if this necessary element of the mosaic were a theory, the process of scientific change would never begin in the first place. Suppose there is a community that accepts only one belief and employs no method whatsoever; this community has no expectations whatsoever. It is obvious that the mosaic of this community will never acquire another element. On the one hand, in order for new theories to become accepted into the mosaic, the mosaic must contain at least one method (by the second law). On the other hand, in order for the mosaic to acquire a new method, there must be not only accepted theories, but also at least one other employed method (by the third law). Indeed, if we recall the historical examples of the third law that we have discussed, we will see that new methods become employed when they are deductive consequences of accepted theories and at least one other employed method. Thus, the necessary (indispensable) element cannot be a theory – it must be a method.

This reason for Necessary Method theorem (Barseghyan-2015) was formulated by Hakob Barseghyan in 2015.1

If a reason supporting this theory is missing, please add it here.

Questions About This Theory

There are no higher-order questions concerning this theory.

If a question about this theory is missing, please add it here.

References

- a b c d e f g h i Barseghyan, Hakob. (2015) The Laws of Scientific Change. Springer.

- ^ Popper, Karl. (1963) Conjectures and Refutations. Routledge.

- ^ Kuhn, Thomas. (1962) The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Lakatos, Imre. (1970) Falsification and the Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes. In Lakatos (1978a), 8-101.

- a b Barseghyan(2015)