Necessary Epistemic Elements

Are there epistemic elements that are necessarily part of any mosaic? What epistemic elements, if any, are necessary for the process of scientific change to occur?

What epistemic elements, if any, are necessary for the process of scientific change to occur?

In the scientonomic context, this question was first formulated by Hakob Barseghyan in 2015. The question is currently accepted as a legitimate topic for discussion by Scientonomy community.

In Scientonomy, the accepted answer to the question is:

- In order for the process of scientific change to be possible, the mosaic must necessarily contain at least one employed method.

Contents

Broader History

Although the scientonomic notion of necessary mosaic elements is unique to scientonomy, the notion of necessary knowledge has been covered extensively within the philosophy of science. In Descartes’ Meditations, he presents the famous cogito ergo sum argument as a justification for the a priori necessity of existential knowledge of some aspect of ‘the self’ irrespective of physical experience. He argues that, even if one doubts the existence and nature of the physical world, they still have knowledge of at least one objective truth in the world, namely, knowledge of their own intellectual existence. Likewise, Leibniz used his principle of sufficient reason to argue for the a priori necessity of the Uniformity of Nature, that is, that we know the universe behaves in similar ways under similar circumstances. He argued that if we accept his principle, we are lead to conclude that similar circumstances yield similar phenomena as there is a similar reason for the same phenomena to obtain. Kant also introduced his a priori forms, universal causation and substance-property dualism, as necessary components of our understanding of physical reality. The conception of necessary elements in scientific mosaics is analogous to these notions of a priori necessary metaphysical knowledge of the world.

Scientonomic History

Acceptance Record of the Question

| Community | Accepted From | Acceptance Indicators | Still Accepted | Accepted Until | Rejection Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scientonomy | 1 January 2016 | This is when the community accepted its first answer to the question, the Non-Empty Mosaic theorem, which indicates that the question is itself considered legitimate. | Yes |

All Direct Answers

If a direct answer to this question is missing, please click here to add it.

Accepted Direct Answers

Suggested Modifications

Current View

In Scientonomy, the accepted answer to the question is Necessary Method theorem (Barseghyan-2015).

Necessary Theories

Necessary Method theorem (Barseghyan-2015) states: "In order for the process of scientific change to be possible, the mosaic must necessarily contain at least one employed method."

According to the non-empty mosaic theorem, there must be at least one element present in a mosaic. The Necessary Method theorem specifies that this element must be a method. That is, "one method is a must for the whole enterprise of scientific change to take off the ground".1p. 228

What would this method be? As per Barseghyan (2015):

This necessary method cannot be substantive. Since a substantive method is necessarily based on at least one contingent proposition, it is not a necessary element of any mosaic. Indeed, any substantive method can become employed after the acceptance of those contingent propositions on which it is based. Of course, in some mosaics, substantive methods can also be present from the outset. Moreover, it is quite likely that even the earliest of mosaics tacitly contained some primitive substantive methods (e.g. “trust your senses”, or “trust the chieftain”). Yet, the key theoretical point is that no substantive method is necessarily part of any mosaic, for a substantive method can become employed after the acceptance of the theories on which it is based.

Therefore, the necessary method is not substantive, but procedural, i.e. it doesn’t presuppose any contingent propositions. But it is a procedural method of a very special kind in that it cannot presuppose any propositions whatsoever: "the method that is necessarily present in any mosaic is not based on any propositions".1p. 230

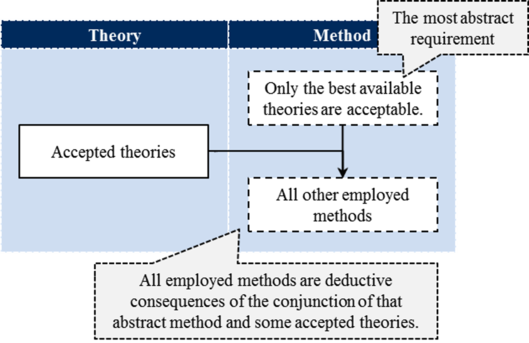

In other words, it must be the most abstract of all methods. Any concrete method is an implementation of a more abstract method. Any concrete method is a logical consequence of the conjunction of some accepted theories and that abstract method (by the third law). Thus, a concrete method can become employed after the acceptance of the propositions on which it is based. Therefore, what we are looking for is the most abstract of all possible requirements.

We have come across that requirement on many occasions: the most abstract requirement to accept only the best available theories. This basic requirement is the most abstract of all, for it does not presuppose any other methods or theories. It is not surprising given that this abstract method is only a restatement of the definition of acceptance: this abstract method basically says that a theory is acceptable when it is the best available description of its object. But since this abstract requirement isn’t based on any theories, it cannot become accepted; it must be built into any mosaic from the outset.

As vague and unrestricting as this method is, it nevertheless performs two very important functions. First, it indicates the main goal of the whole scientific enterprise – the acquisition of best available descriptions. Second, being a link between accepted theories and more concrete methods, it allows us to modify our methods as we learn new things about the world, i.e. it allows for concrete methods to become employed as we accept new theories. In short, it is this abstract requirement that makes the process of scientific change possible.1pp. 230-231

That is, any other method can be conceived as a deductive consequence of the conjunction of this abstract method and some accepted theories:

Related Topics

It has the following sub-topic(s):