Contextual Appraisal theorem (Barseghyan-2015)

This is an answer to the question Nature of Appraisal that states "Theory assessment is an assessment of a proposed modification of the mosaic by the method employed at the time."

Contextual Appraisal theorem was formulated by Hakob Barseghyan in 2015.1 It is currently accepted by Scientonomy community as the best available answer to the question.

Contents

Broader History

The phenomenon of context dependence in science has been described and emphasized by many authors, notably by Helen Longino.2

By the traditional comparativist account of theory appraisal, explains Barseghyan, "all that we need for a theory assessment is two competing theories, some method of assessment, and some relevant evidence. Yet, if we refer to the laws of scientific change, we will see that this list is incomplete. What is missing from this list is the scientific mosaic of the time. What the traditional version of comparativism doesn’t take into account is that, in reality, all theory assessment takes place within a specific historical context, i.e. within the scientific mosaic of the time".1p. 184

In fact, Barseghyan notes that "as early as in The Logic of Scientific Discovery, Popper points out that it is the modifications of a theoretical system that should be assessed, not the system itself. Surely, the central requirement of Popper’s system – the requirement of falsifiability – is applicable to an individual theory ... yet, Popper realizes that falsifiability alone doesn’t allow distinguishing between two competing theories when both are falsifiable and, thus, he formulates additional rules of theory appraisal which are essentially comparative".1pp. 186 Although Popper thus subscribes to the aforementioned comparativist view, Barseghyan believes he "inches towards the contextual appraisal view when he devises a rule that applies only to theory modifications: he prescribes that a theoretical system should be modified in such a fashion that the overall empirical content of the system is not diminished". And, continues Barseghyan, Popper "comes even closer to the contextual appraisal view in his Conjectures and Refutations, where he concedes that in any experimental situation scientists “rely if only unconsciously on… a considerable amount of background knowledge”.3p. 322".1pp. 186 While "it is nowadays common knowledge that any theory assessment presupposes some “unproblematic” background knowledge," Barseghyan emphasizes that "this background knowledge is often presented as a matter of choice or agreement, or, as Popper would have it, as a result of “methodological decisions”.3pp. 151, 322–330. Yet, it must be clear that new generations of scientists do not choose their background knowledge, for they are in no position to start from scratch. What they deal with is the existing scientific mosaic: they take it where they find it and try only to modify it by replacing some of its elements by new elements". This final point is reflected in the contextual appraisal theorem.1p. 186

Kuhn also gets close to the "contextualist" account, for example, when he stresses that our task is not to "evaluate an individual belief (for we are incapable of doing so), but to evaluate the change of belief".4pp. 112-1151pp. 186-7 Yet he does not entirely subscribe to the contextual appraisal view. For Kuhn, accepted theories and employed methods (our scientific mosaic) "play a role in theory assessment only during the so-called periods of normal science," but his view on their role in theory assessment during periods of scientific revolution is "extremely ambiguous".1p. 187

Lakatos also comes quite close to the contextual appraisal view, especially considering how his "famous three rules apply to modifications in a research programme".1p. 187 But, Barseghyan explains, "he isn’t quite there either, since he doesn’t see any significant difference between accepted and unaccepted research programmes, for according to Lakatos scientists evaluate not only modifications in the mosaic of accepted theories and employed methods, but modifications in any research programme. In his view, two research programmes are always on equal footing regardless of which of the two is currently accepted".1p. 187

Hence, although many thinkers have come quite close to accepting our contextual appraisal view, it is fair to say that it "is yet to be fully appreciated".1p. 187

Scientonomic History

Acceptance Record

| Community | Accepted From | Acceptance Indicators | Still Accepted | Accepted Until | Rejection Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scientonomy | 1 January 2016 | The theorem became de facto accepted by the community at that time together with the whole theory of scientific change. | Yes |

Question Answered

Contextual Appraisal theorem (Barseghyan-2015) is an attempt to answer the following question:

See Nature of Appraisal for more details.

Description

The traditional version of comparativism holds that when two theories are compared it doesn’t make any difference which of the two is currently accepted. In reality, however, the starting point for every theory assessment is the current state of the mosaic. Every new theory is basically an attempt to modify the mosaic by inserting some new elements into the mosaic and, possibly, by removing some old elements from the mosaic. Therefore, what gets decided in actual theory assessment is whether a proposed modification is to be accepted. In other words, we judge two competing theories not in a vacuum, as the traditional version of comparativism suggests, but only in the context of a specific mosaic. It is this version of the comparativist view that is implicit in the laws of scientific change.1p. 184

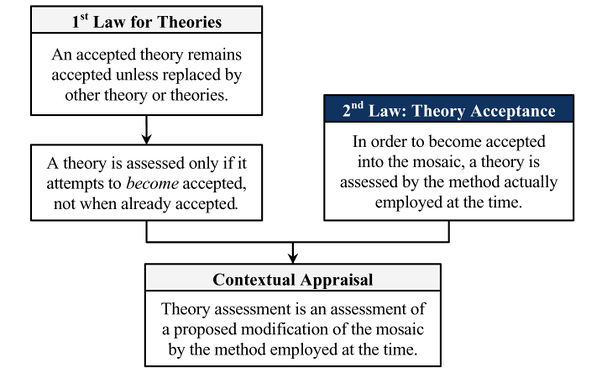

Theory assessment is an assessment of a proposed modification of the scientific mosaic by the method employed at the time. By the first law, a theory already in the mosaic is no longer appraised. By the second law, it is only assessed when it first enters the mosaic (see the detailed deduction below).1pp. 185-196

Barseghyan does note the following: "if, for whatever reason, we need to compare two competing theories disregarding the current state of the mosaic, we are free to do so, but we have to understand that in actual scientific practice such abstract comparisons play no role whatsoever. Any theory assessment always takes into account the current state of the mosaic".1pp. 186

The gist of this theory can be illustrated by the following examples.

Eucharist Episode

Barseghyan (2015) provides another rich illustration for the Contextual Appraisal theorem with "the famous Eucharist episode which took place in the second half of the 17th century," which is a subtler important piece of the already difficult scientonomic case of the 18th-century transition from Cartesian to Newtonian natural philosophy.1p. 190 Barseghyan describes the episode as follows:

This episode has been often portrayed as a clear illustration of how religion affects science. In particular, the episode has been presented as though the acceptance of Cartesianism in Paris was delayed due to the role played by the Catholic Church. It is a historical fact that Descartes’s natural philosophy was harshly criticized by the Church. In 1663, his works were even placed on the Index of Prohibited Books and in 1671 his conception was officially banned from schools. Thus, at first sight, it may appear as though the acceptance of the Cartesian science in Paris was indeed hindered by religion. Yet, upon closer scrutiny, it becomes obvious that this interpretation is too superficial. When Descartes constructed his natural philosophy, it soon turned out that it had a very troubling consequence: it wasn’t readily reconcilable with the doctrine of transubstantiation accepted by the Aristotelian-Catholic scientific community of Paris. The idea of transubstantiation was proposed by Thomas Aquinas in his Summa Theologiae as an explanation of one of the Christian dogmas – namely, that of the Real Presence which states that, in the Eucharist, Christ is really present under the appearances of the bread and wine (i.e. literally, rather than metaphorically or symbolically).

In his explanation of Real Presence, Aquinas employed Aristotelian concepts of substance and accident. In particular, he stated that in the Eucharist the consecration of bread and wine effects the change of the whole substance of the bread into the substance of Christ’s body and of the whole substance of the wine into the substance of his blood. Thus, what happens in the Eucharist is transubstantiation – a transition from one substance to another. As for the accidents of the bread and wine such as their taste, color, smell etc., Aquinas held that they remain intact, for transubstantiation doesn’t affect them. The doctrine of transubstantiation soon became the accepted Catholic explanation of the Real Presence.

The problem was that Descartes’s theory of matter didn’t provide any mechanism similar to that stated in the doctrine of transubstantiation. To be more precise, it followed from Descartes’s original theory that transubstantiation was impossible. Recall that, according to Descartes, the only principal attribute of matter is extension: to be a material object amounts to occupying some space. It follows from this basic axiom that accidents such as smell, color, or taste are effects produced upon our senses by the configuration and motion of material particles. In other words, we simply cannot perceive the accidents of bread and wine unless there is bread and wine in front of us. What makes bread what it is, what constitutes its substance (to use Aristotle’s terms) is a specific combination of material particles; and the same goes for wine. Thus, when the substance of bread changes into the substance of Christ’s body, in the Cartesian theory, it means that some combination of particles which constitutes the bread changes into another combination of particles which constitutes Christ’s body. The key point here is that, in Descartes’s theory, it is impossible for Christ’s body to have the appearance of bread, since the appearance is merely an effect produced by that specific combination of particles upon our senses; Christ’s body and blood simply cannot produce the accidents of bread and wine. Obviously, on this point, Descartes’s theory was in conflict with the doctrine of transubstantiation.

This conflict became the focal point of criticism of Descartes’s theory. To a 21st-century reader used to a clear-cut distinction between science and religion this may seem a purely religious matter. Yet, in the second half of the 17th century, this was precisely a scientific concern. The crucial point is that back then theology wasn’t separate from other scientific disciplines: the scientific mosaic of the time included many theological propositions such as “God exists”, “God is omnipotent”, or “God created the world”. These propositions where part of the mosaic just as any other accepted proposition. If we could visit 17th-century Paris, we would see that the dogma of Real Presence and the doctrine of transubstantiation weren’t something foreign to the scientific mosaic of the time – they were accepted parts of it alongside such propositions as “the Earth is spherical”, “there are four terrestrial elements”, “there are four bodily fluids” and so on. Thus, Descartes’s theory was in conflict not with some “irrelevant religious views” but with a key element of the scientific mosaic of the time, the doctrine of transubstantiation.

More precisely, the problem was that back then no theory was allowed to be in conflict with the accepted theological propositions. This latter requirement was part of the method of the time. The requirement strictly followed from the then-accepted belief that theological propositions are infallible.

Yet, eventually, the Cartesian natural philosophy did become accepted in Paris. If the laws of scientific change are correct, it could become accepted only with a special patch that would reconcile it with the doctrine of transubstantiation. It is not clear as to what exactly this patch was. To be sure, there is vast literature on different Cartesian solutions of the problem: the solutions proposed by Descartes, Desgabets, and Arnauld are all well known.359 However, I have failed to find a single historical narrative revealing which of these patches became accepted in the mosaic alongside the Cartesian natural philosophy circa 1700.360 Based on the available data, I can only hypothesize that the accepted patch was the one proposed by Arnauld in 1671. According to Arnauld’s solution, the Cartesian natural philosophy concerns only the natural course of events. However, since God is omnipotent, he is able to alter the natural course of events. Thus, he can turn bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ even if that is not something that can be expected naturally. Moreover, since our capacity of reason is limited, God can do things that are beyond our reason. Therefore, it is possible for Christ to be really present under the accidents of the bread and wine without our being able to comprehend the mechanism of that presence.361 One reason why I think that this could be the accepted patch is that a similar solution was also proposed by both Régis and Malebranche.362 The latter basically held that what happens in the Eucharist is a miracle and is not to be explicated in philosophical terms. In this context, the position of Malebranche is especially important for, at the time, his Recherche de la Vérité was among the main Cartesian texts studied at the University of Paris.363 Again, I cannot be sure that the accepted patch was exactly that of Arnauld and Malebranche; only closer scrutiny of the curriculum of Paris University in 1700-1740 as well as other relevant sources can settle this issue. Yet, the laws of scientific change tell us that there should be one patch or another – the Cartesian natural philosophy couldn’t have been accepted without one.

In short, initially the Cartesian theory didn’t satisfy the requirements implicit in the mosaic of the time, namely it was in conflict with one of those propositions which were not supposed to be denied. Thus, the acceptance of Descartes’s theory was hindered not because “dogmatic clergy” didn’t like it on some mysterious religious grounds, but because initially it didn’t satisfy the requirements of the time.

This point will become clear if we turn our attention to the scientific mosaic of Cambridge of the same time period. Circa 1660, the mosaics of Paris and Cambridge were similar in many respects. For one, they both included all the elements of the Aristotelian-medieval natural philosophy. In addition, they shared the basic Christian dogmas, such as the dogma of Real Presence. Yet, they were different in one important respect: whereas the mosaic of Paris included the propositions of Catholic theology, the mosaic of Cambridge included the propositions of Anglican theology. Namely, the Cambridge mosaic didn’t include the doctrine of transubstantiation. In that mosaic, the Cartesian theory was only incompatible with the Aristotelian-medieval natural philosophy which it aimed to replace.

This difference proved crucial. Whereas reconciling the Cartesian natural philosophy with the doctrine of transubstantiation was a challenging task, reconciling it with the dogma of Real Presence wasn’t difficult. One such reconciliation was suggested by Descartes himself and was developed by Desgabets. The idea was that the bread becomes the body of Christ by virtue of being united with the soul of Christ, while the material particles of the bread remain intact. For the Catholic, this solution was unacceptable, for it denied the doctrine of transubstantiation and, therefore, was a heresy. Yet, for the Anglican, this solution could be acceptable, since the doctrine of transubstantiation wasn’t part of the Anglican mosaic. Thus, whereas the Catholic was faced with a seemingly insurmountable problem of reconciling the Cartesian natural philosophy with the doctrine of transubstantiation, the Anglican didn’t have that problem. This explains why the whole Eucharist case was almost exclusively a Catholic affair.

This episode illustrates the main point of the contextual appraisal theorem: a theory is assessed only in the context of a specific mosaic and the outcome of the assessment depends on the state of the mosaic of the time.1p. 190-196

New quantum theories

Barseghyan's deduction of the contextual appraisal theorem can be further understood through a brief example. Consider a situation wherein "the proponents of some alternative quantum theory argue that the currently accepted theory is no better than their own quantum theory".1p. 185 But, importantly, we notice that they are taking theory assessment out of its historical context! "Particularly," Barseghyan comments, "they ignore the phenomenon of scientific inertia – they ignore that, in order to remain in the mosaic, the accepted theory doesn’t need to do anything (by the first law for theories) and that it is their obligation to show that their contender theory is better (by the second law)".1p. 185

Galileo's heliocentricism

The depiction of Galileo as a hero, standing up against church authorities to present his "clearly superior" position, is well-known.1p. 187 However, as Barseghyan rightly notes, it fails to take the contemporaneous scientific mosaic of Galileo's community into account. The traditional account, placing both theories aganist each other in a vacuum, "failed to appreciate both that theory assessment is an assessment of a proposed modification and that a theory is assessed by the method employed at the time. Once we focus our attention on the state of the scientific mosaic of the time," though, "it becomes obvious that the scientific community of the time simply couldn’t have acted differently".1p. 188

Let's consider the scientific mosaic circa the 1610s. It consisted of many interconnected Aristotelian-medieval theories, including geocentrism, which "was a deductive consequence of the Aristotelian law of natural motion and the theory of elements".1p. 188

So, "it was impossible to simply cut geocentrism out of the mosaic and replace it with heliocentrism – the whole Aristotelian theory of elements would have to be rejected as well. And it was only made more difficult because "the theory of elements itself was tightly connected with many other parts of the mosaic," such as the possibility of transformation of elements and the medical theory of the time (four humours).1p. 189 "In short," summarizes Barseghyan, "in order to make the rejection of geocentrism possible, a whole array of other elements of the Aristotelian-medieval mosaic would have to be rejected as well".1p. 189

Now by the first law for theories and the theory rejection theorem, "only the acceptance of an alternative set of theories could defeat the theories of the Aristotelian-medieval mosaic".1p. 189 "Unfortunately for Galileo," concludes Barseghyan, "at the time there was no acceptable contender theory comparable in scope with the theories of the Aristotelian-medieval mosaic ... Galileo didn’t have an acceptable replacement for all the elements of the mosaic that had to be rejected together with geocentrism ... The traditional interpretation of this historical episode failed to appreciate this important point and, instead, preferred to blame the dogmatism of the clergy".1p. 189

Another key problem with the typical presentation of this episode is its assessment, "not by the implicit requirements of the time, but by the requirements of the hypothetico-deductive method, which became actually employed a whole century after the episode took place. Namely, Galileo was said to have shown the superiority of the Copernican heliocentrism by confirming some of its novel predictions," which, by the traditional account, was considered "a clear-cut indication of the superiority of the Copernican hypothesis".1p. 189

Yet, Barseghyan's more careful study of the episode reveals the following: "the requirements of hypothetico-deductivism had little in common with the actual expectations of the community of the time. Although the task of reconstructing the late Aristotelian-medieval method of natural philosophy is quite challenging and may take a considerable amount of labour, one thing is clear: the requirement of confirmed novel predictions was not among implicit expectations of the community of the time. Back then, theories simply didn’t get assessed by their confirmed novel predictions".1pp. 189-90 And we note that important point becomes apparent through the contextual appraisal theorem.Reasons

Reason: Deduction of the Contextual Appraisal theorem

Barseghyan presents the following description of the deduction of the contextual appraisal theorem:

By the second law, in actual theory assessment a contender theory is assessed by the method employed at the time ... In addition, it follows from the first law for theories that a theory is assessed only if it attempts to enter into the mosaic; once in the mosaic, the theory no longer needs any further appraisal. In this sense, the accepted theory and the contender theory are never on equal footing, for it is up to the contender theory to show that it deserves to become accepted. In order to replace the accepted theory in the mosaic, the contender theory must be declared superior by the current method; to be “as good as” the accepted theory is not sufficient.

This reason for Contextual Appraisal theorem (Barseghyan-2015) was formulated by Hakob Barseghyan in 2015.1

If a reason supporting this theory is missing, please add it here.

Questions About This Theory

There are no higher-order questions concerning this theory.

If a question about this theory is missing, please add it here.

References

- a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Barseghyan, Hakob. (2015) The Laws of Scientific Change. Springer.

- ^ Longino, Helen. (1990) Science as Social Knowledge: Values and Objectivity in Scientific Inquiry. Princeton University Press.

- a b Popper, Karl. (1963) Conjectures and Refutations. Routledge.

- ^ Kuhn, Thomas. (2000) The Road Since Structure: Philosophical Essays, 1970-1993, with Autobiographical Interview. Edited by J. Conant & J. Haugeland. The University of Chicago Press.