Synchronism of Method Rejection theorem (Barseghyan-2015)

This is an answer to the question Synchronism vs. Asynchronism of Method Rejection that states "A method becomes rejected only when some of the theories, from which it follows, also become rejected."

Synchronism of Method Rejection theorem was formulated by Hakob Barseghyan in 2015.1 It is currently accepted by Scientonomy community as the best available answer to the question.

Contents

Scientonomic History

Acceptance Record

| Community | Accepted From | Acceptance Indicators | Still Accepted | Accepted Until | Rejection Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scientonomy | 1 January 2016 | The theorem became de facto accepted by the community at that time together with the whole theory of scientific change. | Yes |

Question Answered

Synchronism of Method Rejection theorem (Barseghyan-2015) is an attempt to answer the following question: When a method is rejected, must it be the case that a theory has also been rejected?

See Synchronism vs. Asynchronism of Method Rejection for more details.

Description

The principle of this theorem is first introduced in Barseghyan (2015). We recall that "there are two somewhat distinct scenarios of method employment. In the first scenario, a method becomes employed when it strictly follows from newly accepted theories. In the second scenario, a method becomes employed when it implements the abstract requirements of some other employed method by means of other accepted theories. It can be shown that method rejection is only possible in the first scenario; no method can be rejected in the second scenario. Namely, it can be shown that method rejection can only take place when some other method becomes employed by strictly following from a new accepted theory; the employment of a method that is not a result of the acceptance of a new theory and is merely a new implementation of some already employed method cannot possibly lead to a method rejection."1p. 174

As per Barseghyan, it is important to note that "two implementations of the same method are not mutually exclusive and the employment of one doesn’t lead to the rejection of the other".1p. 176 Barseghyan illustrates this nicely with the example of cell-counting methods (see below). Furthermore, he writes, "an employment of a new concrete method cannot possibly lead to a rejection of any other employed method. Indeed, if we take into account the fact that a new concrete method follows deductively from the conjunction of an abstract method and other accepted theories, it will become obvious that this new concrete method cannot possibly be incompatible with any other element of the mosaic. We know from the zeroth law that at any stage the elements of the mosaic are compatible with each other. Therefore, no logical consequence of the mosaic can possibly be incompatible with other elements of the mosaic. But the new method that implemented the abstract method is just one such logical consequence".1p. 176-7

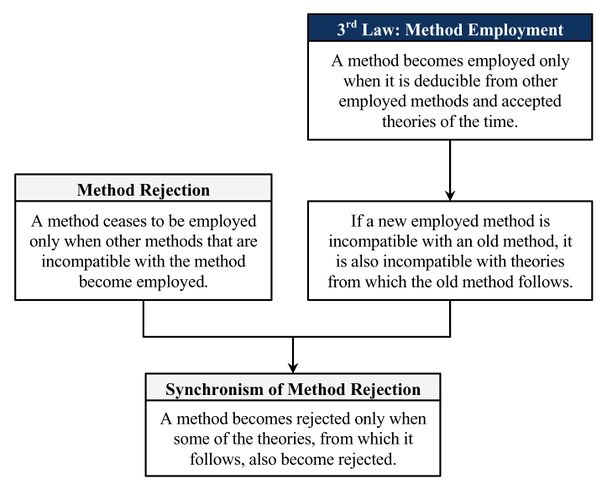

According to the synchronism of method rejection theorem, a method becomes rejected only when some of the theories from which it follows become rejected. By the method rejection theorem, a method is rejected when other methods incompatible with it become employed. By the Third Law, this can happen only when some of the theories from which it follows are also rejected.1p. 177-183

The gist of this theory can be illustrated by the following examples.

Transition from the blind trial method to the double-blind trial method

As Barseghyan notes, it can be tempting to say that the double blind trial method replaced the blind trial method. But this is not a correct explication of the method dynamics at play. Barseghyan provides a more detailed explanation in this historical example that helps to explain the synchronism of method rejection theorem. He begins:

To be sure, the blind trial method was replaced in the mosaic, but not by the double-blind trial method. Rather, it was replaced by the abstract requirement that when assessing a drug’s efficacy one must take into account the possible experimenter’s bias. The employment of the double-blind trial method was due to the fact that it specified this abstract requirement. Its employment per se had nothing to do with the rejection of the blind trial method.2p. 178

He continues his explanation with a closer look at the blind trial method:

Therefore, Barseghyan concludes, "the double-blind trial method had nothing to do with the rejection of the blind trial method. By the time the double-blind trial method became employed, the blind trial method had already been rejected. So even if we had never devised the double-blind trial method, the blind trial method would have been rejected all the same".1p. 180 In summary, "the rejection of the blind trial method took place synchronously with the rejection of the theory on which it was based".1p. 180 Hence, this is a historical example of the synchronism of method rejection theorem.Recall the blind trial method which required that a drug’s efficacy is to be shown in a trial with two groups of patients, where the active group is given the real pill, while the control group is given a placebo. Implicit in the blind trial method was a clause that it is ok if the researchers know which group is which. This clause was based on the tacit assumption that the researchers’ knowledge cannot affect the patients and, thus, cannot void the results of the trial. Although this assumption was hardly ever expressed, it is safe to say that it was taken for granted – we would allow the researchers to know which group of patients is which until we learned about the phenomenon of experimenter’s bias...

Once we learned about the possibility of experimenter’s bias, the blind trial method became instantly rejected. More precisely, the acceptance of the experimenter’s bias thesis immediately resulted in the abstract requirement that, when assessing a drug’s efficacy, one must take the possibility of the experimenter’s bias into account. Consequently, two elements of the mosaic became rejected: the blind trial method and the tacit assumption that the experimenters’ knowledge doesn’t affect the patients and cannot void the results of trials...

Now, the experimenter’s bias thesis yielded the new abstract requirement to take into account the possible experimenter’s bias. This requirement, in turn, replaced the blind trial method with which it was incompatible (by the method rejection theorem).1p. 178-80

Cell Counting: What happens when the same abstract requirement gets implemented by several concrete methods?

Barseghyan answers this question using the following historical example:

Once we understood that the unaided human eye is incapable of obtaining data about extremely minute objects (such as cells or molecules), we were led to an employment of the abstract requirement that the counted number of cells is acceptable only if it is acquired with an “aided” eye. This abstract requirement has many different implementations such as the counting chamber method, the plating method, the flow cytometry method, and the spectrophotometry method. What is interesting from our perspective is that these different implementations are compatible with each other – they are not mutually exclusive. In fact, a researcher can pick any one of these methods, for these different concrete methods are connected with a logical OR. Thus, the number of cells is acceptable if it is counted by means of a counting chamber, or a flow cytometer, or a spectrophotometer. The measured value is acceptable provided that it satisfies the requirements of at least one of these methods ... To generalize the point, different implementations of the same abstract method cannot possibly be in conflict with each other, for any concrete method is a logical consequence of some conjunction of the abstract method and one or another accepted theory (by the third law).2p. 175-6

Aristotelian-Medieval experimentation

"The belief that the nature of a thing cannot be properly studied if it is placed in artificial conditions," Barseghyan writes, was central in Aristotelian-Medieval thought thanks to the strict distinction between natural and artificial in the Aristotelian-Medieval mosaic.1p. 180-1 Since it was understood that, "when placed in artificial conditions, a thing does not behave as it is prescribed by its very nature, but as designed by the craftsman", it was accepted in the Aristotelian-Medieval mosaic that "experiments can reveal nothing about the natures of things".1p. 181

Barseghyan notes that a "requirement that follows from this belief is that an acceptable hypothesis that attempts to reveal the nature of a thing cannot rely on experimental data; the nature of a thing is to be discovered only by observing the thing in its natural, unaffected state any experiments could not constitute proper study or reveal true information about the nature of things".1p. 181 We may call this the no experiments limitation.

Perhaps obviously, the no experiments limitation came to be rejected. The dynamics of this rejection are important as a historical example of the synchronism of method rejection theorem. "Importantly," continues Barseghyan, "the rejection was synchronous with the rejection of the natural/artificial distinction".1p. 182 Particularly, he notes, the two theories that came to replace the Aristotelian natural philosophy – the Cartesian and Newtonian natural philosophies – both assumed that there is no strict distinction between artificial and natural, that is, "that all material objects obey the same set of laws, regardless of whether they are found in nature or whether they are created by a craftsman".1p. 182

In abandoning the artificial/natural distinction, "we also realized that experiments can be as good a source of knowledge about the world as observations. Consequently, we had to modify our method, and accepted the new experimental method: "When assessing a theory, it is acceptable to rely on the results of both observations and experiments".1p. 182 Since the experimental method was incompatible with the previous Aristotelian no-experiments method, that method, by the method rejection theorem, was rejected. The crux of this historical episode, as Barseghyan emphasizes, is that the Aristotelian "limitation was rejected simultaneously with the rejection of the natural/artificial distinction on which it was based – exactly as the synchronism of method rejection theorem stipulates".1p. 182Implementation of an abstract methodd

Barseghyan (2015) introduces the synchronism of method rejection theorem through the following hypothetical example.

Let us start with the following case. Suppose there is a new method that implements the requirements of a more abstract method which has been in the mosaic for a while. By the third law, the new method becomes employed in the mosaic.

Question: what happens to the abstract method implemented by the new method?

The answer is that the abstract method necessarily maintains its place in the mosaic. By the method rejection theorem, a method gets rejected only when it is replaced by some other method which is incompatible with it. But it is obvious that our new method cannot possibly be in conflict with the old method. This is not difficult to show. To say that the new method implements the abstract requirements of the old abstract method is the same as to say that the new method follows from the conjunction of the abstract method and some accepted theories. Yet, if we consider the two methods in isolation, we will be convinced that the abstract Method 1 is a logical consequence of the new Method 2. (When Method 2 implements the requirements of Method 1, Method 1 is necessarily a logical consequence of Method 2.)

To rephrase the point, if a theory satisfies the more concrete requirements of Method 2, it also necessarily satisfies the more abstract requirements of Method 1.2p. 174-5

This hypothetical illustration aligns well with the historical example of the abstract requirement to take the placebo effect into account being implemented through the blind trial method:

Recall, for instance, the abstract requirement that, when assessing a drug’s efficacy, the placebo effect must be taken into account. Recall also its implementation – the blind trial method. It is evident that when the more concrete requirements of the blind trial method are satisfied, the more abstract requirement to take into account the possibility of the placebo effect is satisfied as well. This is because the abstract requirement is a logical consequence of the blind trial method: by testing a drug’s efficacy in a blind trial, we thus take into account the possible placebo effect.2p. 175

Reasons

Reason: Synchronism of Method Rejection Deduction

Barseghyan explains the deduction:1pp. 177-178

By the method rejection theorem, a method is rejected only when other methods incompatible with the method become employed. Thus, we must find out when exactly two methods can be in conflict. In order to find that out, we must refer to the third law which stipulates that an employed method is a deductive consequence of accepted theories and other methods. Logic tells us that when a new employed method is incompatible with an old method, it is also necessarily incompatible with some of the theories from which the old method follows. Therefore, an old method can be rejected only when some of the theories from which it follows are also rejected.

This reason for Synchronism of Method Rejection theorem (Barseghyan-2015) was formulated by Hakob Barseghyan in 2015.1

If a reason supporting this theory is missing, please add it here.

Questions About This Theory

There are no higher-order questions concerning this theory.

If a question about this theory is missing, please add it here.