The Theory of Scientific Change

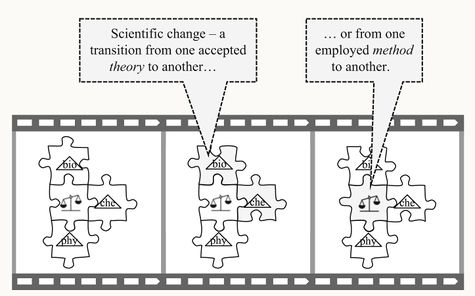

Theory of Scientific Change (TSC) is a descriptive theory that attempts to explain changes in a scientific mosaic, i.e. transitions from one theory to the next and one method to the next. The current theory of scientific change explains many different aspects of the process such as theory acceptance and method employment, scientific inertia and compatibility, splitting and merging of scientific mosaics, scientific underdeterminism, changeability of scientific methods, role of sociocultural factors, and more.

Contents

- 1 Prehistory

- 2 History

- 3 Current View

- 3.1 What is the theory of scientific change?

- 3.2 Axioms

- 3.3 Theorems

- 4 Open Questions

- 5 Related Articles

- 6 Notes

Prehistory

Prehistory here

History

The theory of scientific change (TSC) was proposed by Hakob Barseghyan in his book The Laws of Scientific Change, published in 2015.1 In 2016, Zoe Sebastien resolved an important logical paradox, which necessitated a change to the third law of scientific change.2 At the same time, the definition of theory was also modified to include not only descriptive propositions but also normative propositions (e.g. normative scientific methodologies, ethical beliefs, etc.). As a result, the scope of the TSC was expanded to include also normative beliefs accepted by a community.

Current View

What is the theory of scientific change?

The theory of scientific change (TSC) is a general descriptive social scientific theory of the actual process of scientific change stated in axiomatic deductive form. It is the founding theory of the new field of scientonomy. It was proposed by Hakob Barseghyan in 2015 in his book 'The Laws of Scientific Change'1.

Methods

As in the later works of Larry Laudan 3, the TSC rejects the idea of a fixed universal scientific method, and accepts the idea that the methods of science have changed over time. This rejection is based on clear evidence from the history of science that the methods of science have, in fact, changed 1p. 3-21. In contrast to most earlier views of the process of scientific change, TSC draws a clear distinction between methods, which are the implicit standards actually used in theory assessment, and the normative epistemic methodologies espoused by scientists or philosophers of science. The TSC takes normative methodological prescriptions to be outside its scope. It seeks a purely descriptive account of the methods employed by scientists to assess theories 1p. 12-21. Following the resolution of logical problems by Sebastien 2, it also views the descriptive study of scientific methodologies, and their relationship to employed methods, as within its scope. The TSC rejects Kuhn4and Laudan's3 distinction between values and methods, asserting that values can more parsimoniously be included within the category of methods. Thus, the value of predictive accuracy is instead seen as the method 'accept theories that are predictively accurate'.

Theory appraisal

The TSC draws a distinction between the process of scientific theory construction, in which new theories are generated or constructed, and that of theory appraisal, in which theories are evaluated by a scientific community. It seeks a descriptive account of the process of theory appraisal, but does not view the process of theory construction as a necessary part of its scope 1p. 21-30. Unlike past usage, the TSC seeks a clear technical vocabulary to categorize the stances that a scientific community can take towards a theory. It proposes three categories: acceptance, use, and pursuit. A theory is said to be accepted if it is taken to be the best available description of its object. A theory is said to be used if it is taken to be an adequate tool for practical application, and to be pursued if it is considered worthy of further development 1p. 30-42.

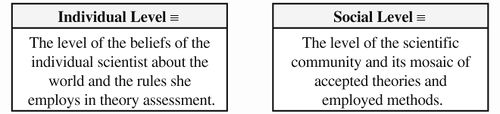

Level of social organization

Rather than individual scientists, the TSC focuses primarily on the behavior of scientific communities. A scientific community consists of individual scientists and their interactions with one another. Past research in the history of science has often focused on prominent individual scientists. The beliefs and decisions of individual scientists are diverse and the relationship between their behavior and that of a scientific community is by no means obvious. Scientific change takes place at the level of the community, when a community as a whole decides to accept a new theory, or employ a new method. This is the reason why the TSC focuses at this level 1p. 43-52. It seeks distinctive historical research methods, such as the analysis of textbooks and encyclopedias, as indicators of the accepted beliefs of a scientific community 1p. 113-120.

Time, fields, and scale

The TSC seeks to account for the process of scientific change during all historical time periods within which a corpus of accepted scientific beliefs existed. It seeks to account for this entire corpus of beliefs. The TSC defines "science" broadly. For example, during the medieval and early modern period, propositions about the natural world and about theological matters were considered part of the same system of beliefs. For those time periods, the TSC takes theological beliefs to be within its purview 1p. 3-21.

Basic tenets of the theory

The TSC begins by positing the existence of a scientific mosaic consisting of the accepted theories and employed methods of a scientific community at some particular time in history. Scientific change is the process by which the contents of the mosaic are altered over time. The TSC posits four laws as its axioms which together account for changes to both theories and methods. These are, The Zeroth Law: The law of compatibility, The First Law: The law of scientific inertia, The Second Law: The law of theory acceptance, and The Third Law: The law of method employment. These laws are summarized briefly here, and are expounded at greater length in their respective encyclopedia articles. A number of theorems have been deduced from these basic laws and they are also summarized here1.

Axioms

The TSC posits four laws as axioms governing the process of change to the scientific mosaic.

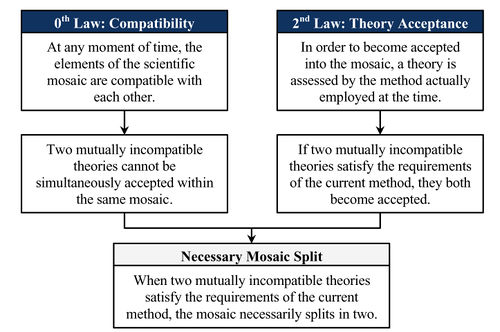

Zeroth Law: The Law of Compatibility

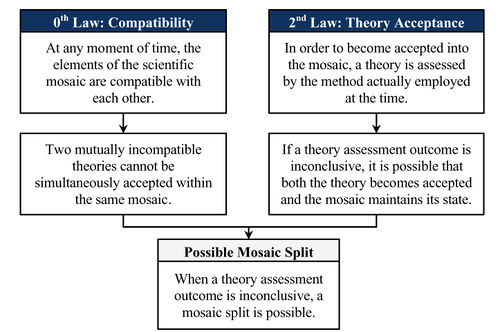

The Zeroth Law, also known as the Law of Compatibility states that at any moment in time, the elements of the scientific mosaic are compatible with one another. These elements include both theories and methods. The compatibility criteria are part of the method of the time 1p. 152-164.

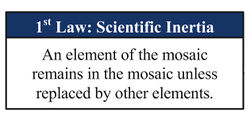

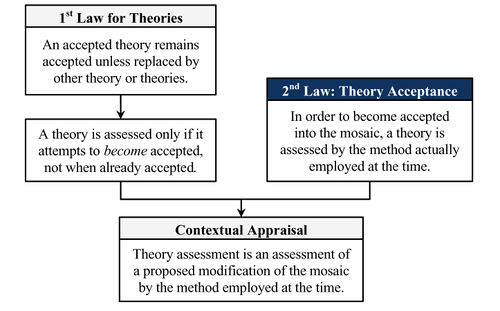

First Law: The Law of Scientific Inertia

The First Law, also known as the Law of Scientific Inertia states that an element of the scientific mosaic remains in the mosaic unless replaced by other elements. These elements include both theories and methods. Replacement takes place in accordance with the Second and Third Laws 1p. 123-129.

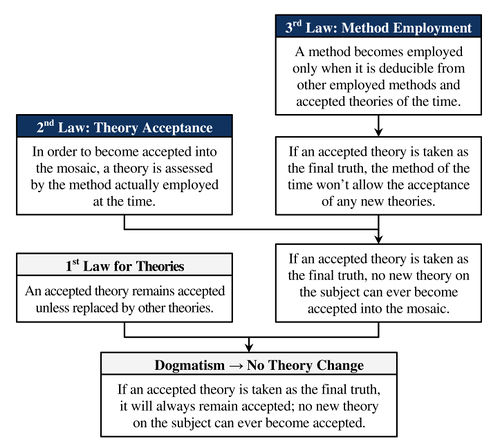

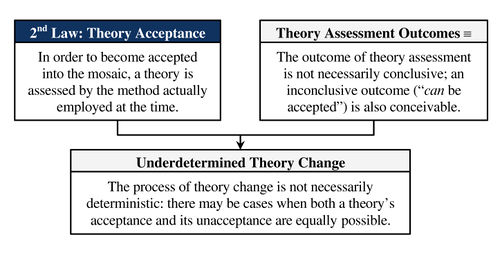

Second Law: The Law of Theory Acceptance

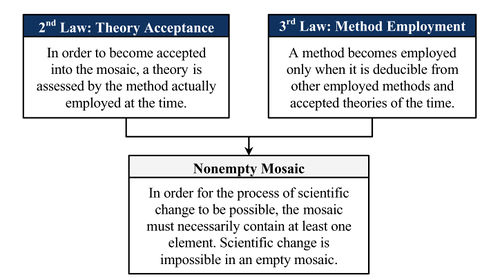

The Second Law, also known as the Law of Theory Acceptance states that in order to become accepted into the scientific mosaic, a theory is assessed by the method actually employed at the time1p. 129-132.

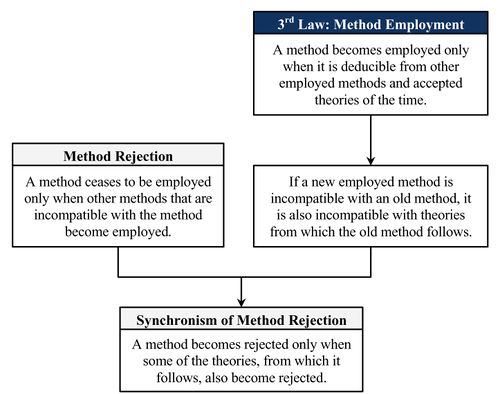

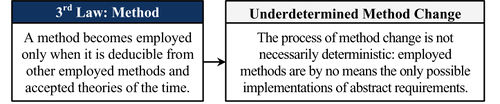

Third Law: The Law of Method Employment

The Third Law, also known as the Law of Method Employment states that a method becomes employed when it is deducible from some subset of other employed methods and accepted theories of the time1p. 132-152.

Theorems

Taking the four laws of scientific change as the starting point, the following theorems about the process of scientific change have so far been deduced 1Chapt. 5.

Rejection of elements

We can deduce three theorems that have to do with the rejection of theories or methods from the scientific mosaic.

Dogmatism theorem

No theory acceptance may take place in a genuinely dogmatic community. Suppose a community has an accepted theory that asserts that it is the final and absolute truth. By the Third Law we deduce the method: accept no new theories ever. By the Second Law we deduce that no new theory can ever be accepted by the employed method of the time. By the First Law, we deduce that the accepted theory will remain the accepted theory forever1p. 165-167.

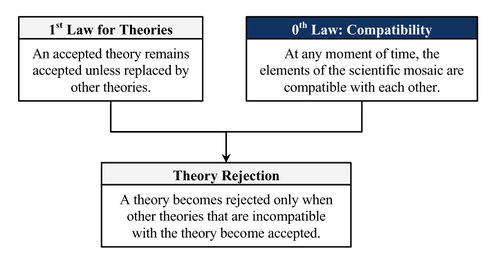

Theory rejection theorem

A theory becomes rejected only when other theories that are incompatible with the theory become accepted. By the First Law for theories, an accepted theory will remain accepted until it is replaced by other theories. By the Zeroth Law, the elements of the scientific mosaic must be compatible with one another. Thus, a theory can only become rejected when it is replaced by an incompatible theory or theories1p. 167-172.

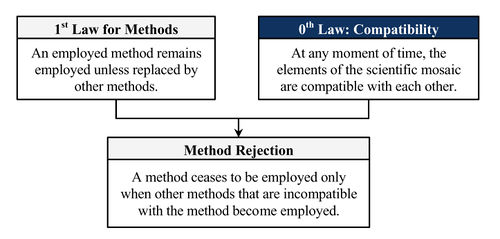

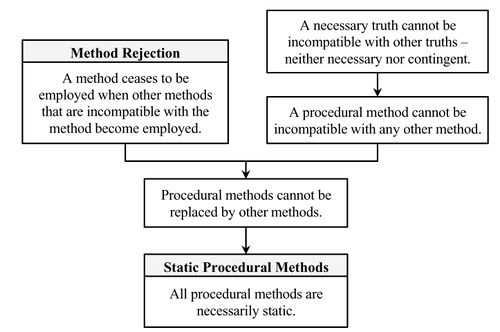

Method rejection theorem

A method ceases to be employed only when other methods that are incompatible with it become employed. By the First Law for methods, an employed method will remain employed until it is replaced by other methods. By the Zeroth Law, the elements of the scientific mosaic must be compatible with one another. Thus, a method can only become rejected when it is replaced by an incompatible method or methods1p. 172-176.

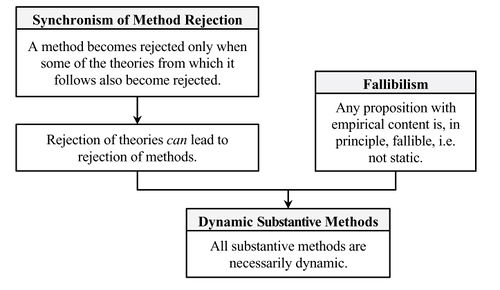

Synchronism of method rejection theorem

A method becomes rejected only when some of the theories from which it follows become rejected. By the method rejection theorem, a method is rejected when other methods incompatible with it become employed. By the Third Law, this can happen only when some of the theories from which it follows are also rejected 1p. 177-183.

Contextual Appraisal

Theory assessment is an assessment of a proposed modification of the scientific mosaic by the method employed at the time. By the First Law, a theory already in the mosaic is no longer appraised. By the Second Law, it is only assessed when it first enters the mosaic1pp. 185-196.

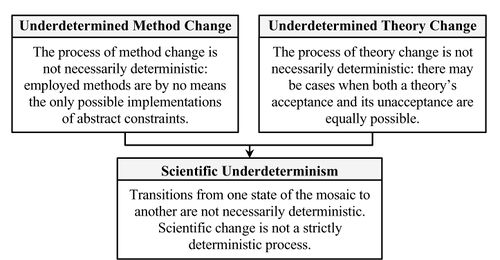

Scientific Underdeterminism

Scientific underdetermination is the thesis that the process of scientific change is not deterministic, and science could have evolved differently than it did. Hypothetically, two scientific communities developing separately could experience an entirely different sequence of successive states of their respective scientific mosaics. Even without the TSC, the implausibility of scientific determinism can be seen by considering the process of theory construction, which is outside the present scope of the TSC. Theory construction requires creative imagination, and the formulation of a given theory is therefore not inevitable. Still, underdetermination can also be inferred as a theorem from the axioms of the TSC 1pp. 196-198.

Underdetermined method change

The third law allows for two distinct scenarios of method employment. A method may become employed because it follows strictly from accepted theories or employed methods, or it may the abstract requirements of some other employed method. This second scenario allows for creative ingenuity and depends on the technology of the times, therefore it may be fulfilled in many ways and allows underdeterminism 1p. 198.

Underdetermined theory change

The process of theory assessment under the TSC is underdetermined for two reasons. First, only theories that are constructed are available for assessment. Whether or not a theory is ever constructed is, at least partly a matter of creativity, and is therefore outside the scope of the TSC. Second, it is at least theoretically possible that a process of theory assessment will be inconclusive. This might be because the employed method of the time is vague, or because it involves multiple criteria, only some of which have been met 1p. 199-200.

Underdeterminism of science

Taken together the theorem of underdetermined method change and the theorem of underdetermined theory change imply that scientific change is not a strictly deterministic process 1p. 201-202.

Mosaic Split and Mosaic Merge

Mosaic split is a scientific change that results when one scientific mosaic splits into two or more mosaics containing incompatible accepted theories or employed methods. This entails that a previously united scientific community bearing a single mosaic becomes two or more communities, each with its own mosaic. Mosaic merge is a scientific change in which two or more mosaics containing incompatible theories or methods become a single united mosaic with compatible theories and methods. This likewise entails the formation of a single community out of two or more 1p.202-216.

Necessary mosaic split

Necessary mosaic split is a form of mosaic split that must happen if it is ever the case that two incompatible theories both become accepted under the employed method of the time. Since the theories are incompatible, under the zeroth law, they cannot be accepted into the same mosaic, and a mosaic split must then occur, as a matter of logical necessity 1p. 204-207.

Possible mosaic split

Possible mosaic split is a form of mosaic split that can happen if it is ever the case that theory assessment reaches an inconclusive result. In this case, a mosaic split can, but need not necessarily, result 1p. 208-213.

Static and Dynamic Methods

A dynamic method is one that is changeable and has changed over the history of science. A static method one that has persisted unchanged throughout that history. A debate which occurred through a series of papers by Larry Laudan and John Worrall identified a distinction between substantive methods and procedural methods. Substantive methods are those which presuppose at least one contingent proposition (i.e. something that could be otherwise, such as a fact or theory about the empirical world) and are therefore changeable. Procedural methods don't presuppose any contingent propositions and rely only on logically necessary truths and therefore must be fixed. The TSC has important implications for this debate 1p.217-225.

Dynamic substantive methods

The thesis of fallibilism asserts that any theory referring to the empirical world is always vulnerable to rejection. The synchronism of method rejection theorem, detailed above, asserts that a method becomes rejected only when some of the theories from which it follows are rejected. Therefore any method that follows from an empirical theory is always vulnerable to rejection. All substantive methods are therefore necessarily also dynamic p. 223-224.

Static procedural methods

The method rejection theorem, detailed above, asserts that a method ceases to be employed when other methods incompatible with the method become employed. By definition, a necessary truth, or tautology, cannot be incompatible with other necessary or contingent truths. Thus, all procedural methods are also static 1p. 224-225.

Necessary Elements

The question of necessary elements is the question of what, if anything, the TSC requires to be theoretically present at the outset, in order for scientific knowledge to get its start1p. 226-233.

Non-empty mosaic theorem

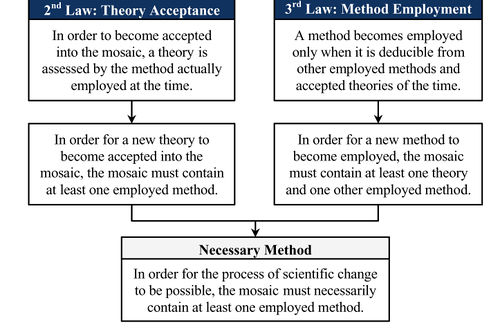

The non-empty mosaic theorem asserts that in order for a process of scientific change to be possible, the mosaic must necessarily contain at least one element. Scientific change is impossible in an empty mosaic. It can be deduced from the second law, which asserts that in order to become accepted into the mosaic, a theory is assessed by the method actually employed at the time, and the third law, which asserts that a method becomes employed only when it is deducible from other employed methods and accepted theories of the time 1p. 226.

Necessary method theorem

The necessary method theorem asserts that the necessary element required by the non-empty mosaic theorem must be a method. It can be deduced from the second law that in order for a new theory to become accepted, the mosaic must contain at least one employed method. It can be deduced from the third law that in order for a new method to become employed, the mosaic must contain at least one theory and one other employed method. Therefore the initial element could only be a method. Barseghyan 1p. 230 suggests that the primordial method might be something extremely general and vague, such as 'accept only the best theories'1p. 228-233.

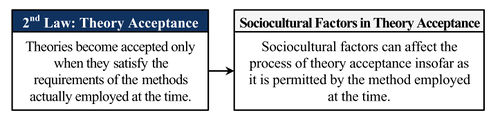

Sociocultural Factors

The role of sociocultural factors as posited by the TSC can be deduced from the second law, which asserts that a theory will be accepted only when it satisfies the employed method of the times. Sociocultural factors can affect the process of theory acceptance insofar as it is permitted by the employed method of the time 1p. 233-240.

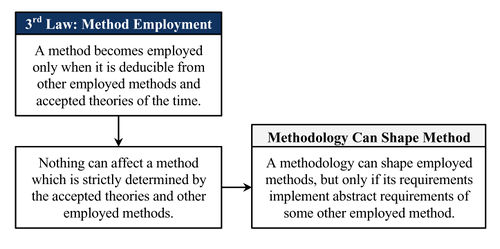

The role of Methodology

The role of methodologies in shaping methods under the TSC is indicated by the third law, under which the employed method is strictly determined by other methods and accepted theories of the time. A methodology can shape employed methods, but only if its requirements implement abstract requirements of some other employed method1p.240-243

.

Open Questions

• Currently, the necessary element theorem states that the method,“only accept the best available theories”, is a necessary element for any mosaic. Are there any necessary theories in addition to this method? It seems as though there must be some necessary analytic theories, because any scientific enterprise assumes a whole network of analytic propositions. Are there any necessary synthetic propositions? If so, this could mean that synthetic a priori knowledge is possible. (Hakob Barseghyan, 2016)

• The Contextual Appraisal Theorem defines “historical context” as “scientific historical context” (i.e, the set of accepted theories and employed methods held at time t). When discussing the influence of socio-cultural factors on the mosaic, however, we shift to a conception of “historical context” which includes non-scientific socio-cultural phenomenon. Should the idea of “historical context” be consistent through the TSC, and if so, how should we define it? Will this alter the Contextual Appraisal Theorem? (Stephen Watt, 2016)

Related Articles

Notes

References

- a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai Barseghyan, Hakob. (2015) The Laws of Scientific Change. Springer.

- a b Sebastien, Zoe. (2016) The Status of Normative Propositions in the Theory of Scientific Change. Scientonomy 1, 1-9. Retrieved from https://www.scientojournal.com/index.php/scientonomy/article/view/26947.

- a b Laudan (1984)

- ^ Kuhn (1977)